The Insider’s Guide to Mastering BERT Fine-Tuning for World-Class Natural Language Understanding (NLU)

Imagine you’re building a virtual assistant, a sophisticated customer service agent, or perhaps a powerful tool to analyze complex medical records. You train your system on thousands of examples, yet when a user throws in a curveball—a slightly ambiguous phrase, a typo, or a request phrased in a way you didn’t explicitly teach it—the whole system collapses.

That feeling of hitting a wall is the historical reality of Natural Language Understanding (NLU). For decades, achieving true reading comprehension in machines was considered an “AI-hard problem” due to the sheer ambiguity and nuance inherent in human communication.

But that challenge has largely been overcome, thanks to a technological revolution built on massive language models and a technique called transfer learning. Today, we’re going to break down the core technology that enables systems to finally understand what we mean, not just what we say: mastering BERT fine-tuning.

What is Natural Language Understanding (NLU) and Why it is Hard?

Natural Language Understanding is a critical subset of the broader field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) in artificial intelligence. While NLP handles foundational elements like morphological analysis and syntax parsing, NLU is specifically focused on machine reading comprehension—the deep interpretation of text. Its strategic significance is that it acts as a semantic translator, transforming messy, unstructured text input into actionable computational output.

Early attempts at NLU, like the STUDENT program (1964) for solving algebra word problems or ELIZA (1965) for dialogue, were limited. ELIZA, for example, relied on superficial parsing and simple keyword substitution, highlighting the difficulty in moving past basic pattern matching to address real-world ambiguity and robust context.

NLU vs. NLP: Understanding the Interpretation Imperative

The central goal of NLU algorithms is the semantic imperative: discerning abstract concepts that are innate in human discourse, moving far beyond computer language syntax. This involves intuiting:

- Emotion

- Effort

- Intent

- Goal

A sophisticated NLU solution needs a comprehensive knowledge base to recognize entities and the complex relationships between them, ensuring that the resulting output (often structured data) is highly refined intelligence suitable for automated reasoning and response generation.

The Foundation of NLU: Key Conversational Tasks

Modern NLU is functionally defined by two core tasks that convert human requests into structured data:

- Intent Recognition (Utterance Classification): Assigning a single, discrete label to the entire input that represents the user’s overarching objective. If a customer asks, “How could I get my money back?”, the system classifies the intent as get_refund.

- Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Slot Filling: This extracts the specific parameters needed to fulfill the intent.

- Entity Extraction: Parsing the input to identify relevant categorical or numerical data. For instance, in the query “I’d like to order three large blue t-shirts,” the model extracts Quantity: 3, Color: Blue, Size: Large, and Item Type: T-Shirt.

- Slot Filling: Using these extracted entities to populate the necessary information slots corresponding to the detected intent (e.g., filling slots in an “order” request). This process streamlines the interaction by allowing the agent to handle complex queries without asking clarifying questions.

The Breakthrough: Why Contextual Embeddings (BERT) Changed Everything

To achieve this level of deep interpretation, models needed to solve two major historical roadblocks: fixed word meanings and long-term memory loss.

Moving Past Static Embeddings (Word2Vec, GloVe)

Before the Transformer revolution, models used static embeddings such as Word2Vec and GloVe. These models map each distinct word to a single, fixed numerical vector, regardless of context.

- Word2Vec/GloVe Limitation: The word “bank” possesses an identical vector representation whether it appears in the context of “river bank” or “bank account.”

- The Polysemy Barrier: This fixed mapping fundamentally limits effectiveness in advanced NLU tasks where accurate interpretation hinges on semantic nuance, making it hard to distinguish, for example, between “Python” (the programming language) and “Python” (the snake).

Solving the “Short-Term Memory” Crisis (The RNN/Gradient Problem)

Older deep learning models, notably Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), used recurrent connections to process sequential data. While an improvement, RNNs suffered from the vanishing gradient problem. During training, if the sequence was long, gradients (signals used to update weights) diminished rapidly, approaching zero.

This gradient decay resulted in “short-term memory,” meaning the network struggled to learn long-range dependencies, as weights corresponding to tokens early in the sequence received extremely weak updates.

Contextual embeddings, exemplified by BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), addressed this. BERT uses deep neural networks to process entire sentences, ensuring the vector assigned to a word changes based on its specific surrounding text. This marked a strategic leap from modeling words to modeling concepts.

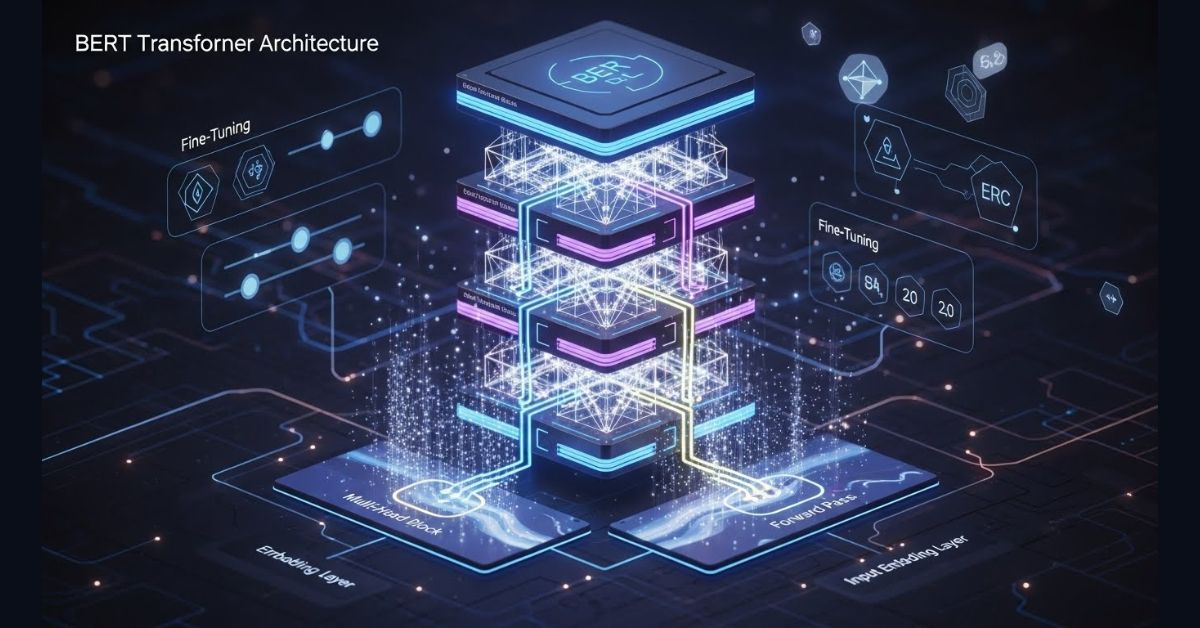

Mastering BERT Fine-Tuning: The Core Methodology

BERT revolutionized NLU by introducing a powerful approach based on massive pre-training and effective transfer learning. The original BERT model comes in large versions with 110 million and 340 million parameters, demonstrating its scale. When you have sufficient computational resources, fine-tuning BERT is the modern solution for almost any downstream NLP application.

The core principle is simplicity: BERT requires minimal architectural changes—typically just the addition of extra fully connected layers, often called a classification head.

Here is the essential workflow:

- The base BERT model is pre-trained on vast unlabeled corpora (like the BookCorpus and English Wikipedia), imbuing it with universal language representations.

- During supervised learning for a specific downstream task (e.g., recognizing intent), the parameters of these new, extra layers are learned from scratch.

- Simultaneously, all parameters in the pretrained BERT model are fine-tuned. This joint parameter update optimally adapts the universal representations to the specific semantics of your target NLU task.

The Fine-Tuning Workflow for Sequence-Level Tasks

Sequence-level tasks require a single outcome for the entire text input.

- Examples: Single text classification (like sentiment analysis) and testing linguistic acceptability (such as judging if “I should study.” is acceptable but “I should studying.” is not). Text pair classification or regression (like Natural Language Inference or Semantic Textual Similarity).

- The Key Token: The special classification token $\langle\mathrm{cls}\rangle$ is used for sequence classification and is always prepended to the input sequence.

- Process: The BERT representation corresponding to the $\langle\mathrm{cls}\rangle$ token encodes the information of the entire input text sequence. This consolidated representation is then fed into a small Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) consisting of fully connected (dense) layers to produce the output distribution (e.g., the likelihood of positive/negative sentiment).

- Text Pair Input: For tasks like Semantic Textual Similarity (STS), which outputs a continuous similarity score (e.g., 5.000 for “A plane is taking off.” and “An air plane is taking off.”), a special $\langle\mathrm{sep}\rangle$ token marks the separation between the two input texts.

The Fine-Tuning Workflow for Token-Level Tasks

Token-level tasks require assigning a label to every individual unit or segment within the input text.

- Example 1: Text Tagging (Part-of-Speech Tagging): If the input is “John Smith’s car is new,” the model tags each word, such as NNP (proper noun), NN (singular noun), and JJ (adjective).

- Process: Unlike sequence tasks, the BERT representation of every token of the input text is fed individually into the same extra fully connected layers to output a label for that specific token. This is fundamental for Named Entity Recognition (NER) and slot filling.

BERT for Question Answering: The Reading Comprehension Machine

Question answering (QA) is another critical token-level application, reflecting machine reading comprehension, famously evaluated using datasets like SQuAD (Stanford Question Answering Dataset).

- The Task: For SQuAD v1.1, the answer is a segment of text (a text span) from a provided passage. Given a passage and a question, the goal is to predict the start and end of that text span.

- Example: Passage: “Mask makers insist that their products… can guard against the virus.” Question: “Who say that N95 respirator masks can guard against the virus?” Answer: “mask makers.”

- Input Structure: The question and the passage are packed as a text pair, separated by the $\langle\mathrm{sep}\rangle$ token.

- Prediction: An additional fully connected layer transforms the BERT representation of any passage token at position $i$ into a scalar score $s_i$ for being the start of the span, and a separate, independent layer transforms it into a scalar score $e_j$ for being the end of the span. These scores are converted into a probability distribution via softmax.

- Output: The model predicts the valid span (from position $i$ to position $j$, where $i \le j$) that yields the highest total score, calculated as $s_i + e_j$.

Strategic Advantages and Advanced NLU Architectures

While BERT established the modern foundation, research continues to refine how we adapt and evaluate these powerful models, particularly in demanding scenarios like conversational AI and few-shot learning.

Optimizing Performance: The Power of Joint Modeling

For conversational systems, intent detection and slot filling are inherently interdependent. Training a single model to perform these jointly (Joint Intent Detection and Slot Filling) is computationally more efficient and typically leads to better performance than training two separate models.

When dealing with complex extraction tasks, like NER or slot filling, how you define and evaluate the output is crucial:

- Token-Based Labeling: The traditional method assigns a label (e.g., B-PER, I-PER) to every single token.

- Span-Based Labeling: The modern, more robust approach classifies continuous segments or spans of text. Span-based metrics are significantly more rigorous and essential for production systems, as they ensure the model correctly identifies the full boundary and classification of the entity, guaranteeing structural integrity in the extracted data.

Few-Shot Learning: Adapting BERT with Retrieval-Based Frameworks

In scenarios requiring rapid adaptation to new domains with minimal training data (few-shot learning), traditional classification models often suffer from catastrophic forgetting or overfitting.

Retrieval-Based Frameworks (Retriever) offer an elegant solution. This method leverages span-level retrieval to match token spans in the input utterance to the most similar labeled spans found in a small, external retrieval index of labeled examples.

Actionable Takeaways for Few-Shot NLU:

- Reduced Retraining: You can adapt the system to a new domain simply by updating the retrieval index, requiring minimal re-training of the core model.

- Robustness: The model is highly robust against overfitting, which is common when data is scarce.

- Interpretability: Crucially, the retrieved examples serve as justifications for the prediction, making the method inherently more interpretable.

- Efficiency: Retrieval methods allow for parallel decoding and potential non-autoregressive speedup, contrasting favorably with slow sequential models.

The Crucial Distinction: Encoder-Only BERT vs. General LLMs

A key strategic finding for modern NLU development concerns the specialized role of encoder-only models like BERT (and its successor, RoBERTa) versus massive Large Language Models (LLMs) built primarily on decoder architectures (like GPT series).

Empirical analysis consistently demonstrates that smaller, specialized encoder-only models fine-tuned for classification and extraction tasks frequently outperform general LLMs on standardized NLU benchmarks like GLUE and SuperGLUE. This superiority is often attributed to the encoder’s ability to capture bidirectional context, which is essential for deep semantic analysis.

While LLMs are phenomenal at generation, for enterprise applications focused strictly on interpretation, classification, and entity extraction at scale, the technical optimum remains the resource-efficient, fine-tuned specialized encoder model.

For instance, the average score of BERT-base on the GLUE benchmark is 79.6, a number that surpasses the performance of the LLAMA2-7B model using zero-shot (46.1) or few-shot (58.7) prompting. Even after supervised fine-tuning (SFT), LLAMA2-7B only reached an average of 78.5 on GLUE.

However, advanced techniques like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), a reinforcement learning method, have shown promise in bridging this gap for LLMs, demonstrating an ability to significantly boost an LLM’s NLU capabilities, in some cases even surpassing strong baselines like BERT-large (average GLUE score 82.1) by achieving scores up to 84.8.

Evaluating Your NLU System: Metrics That Matter

Developing robust NLU is impossible without rigorous evaluation. Choosing the right metric determines whether your model is truly production-ready or simply achieving misleadingly high scores.

Beyond Accuracy: Why Entity/Span-Based F1 is Essential

For classification tasks, metrics derived from True Positives (TP), True Negatives (TN), False Positives (FP), and False Negatives (FN) are standard:

- Accuracy: The ratio of correct predictions to total samples.

- Precision: Measures how often the model’s positive predictions are correct ($T_P / (T_P + F_P)$).

- Recall: Measures how many actual positive samples the model correctly identifies ($T_P / (T_P + F_N)$).

- F1 Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall. This is the most critical metric for NLU, especially when the cost of missing an entity (low recall) is equivalent to the cost of incorrectly identifying a non-entity (low precision).

For structural prediction tasks like Named Entity Recognition (NER) and slot filling, standard token-based metrics or accuracy can be misleading because they might credit a partially identified entity as correct. To enforce high quality, you must use:

- Entity/Span-Based F1: This metric ensures the correctness of the entire entity boundary and its classification label, guaranteeing the structural output is sound before accepting the prediction.

For question answering (QA) systems, two complementary metrics are used:

- Exact Match (EM): Measures the percentage of predictions that perfectly match the reference answer.

- F1 Score: Measures the token overlap between the prediction and the ground-truth answer.

Setting the Standard: Key NLU Benchmarks (GLUE, SuperGLUE, SQuAD)

Standardized benchmark datasets allow the industry to track progress and compare models rigorously:

- SQuAD (Stanford Question Answering Dataset): Evaluates machine reading comprehension. On SQuAD, the best models have demonstrated superhuman precision (F1 score of 92.777 compared to the estimated human baseline of 89.452).

- GLUE (General Language Understanding Evaluation): A collection of nine sentence and sentence-pair NLU tasks, covering tasks like sentiment analysis (SST-2) and testing linguistic acceptability (CoLA).

- SuperGLUE: Introduced after models quickly surpassed the human baseline on GLUE (which was 87.1, with the best model achieving 90.6). SuperGLUE features more challenging tasks requiring advanced reasoning.

Actionable Takeaways for Building Production-Ready NLU

As an expert in the field, my final guidance for implementing NLU today is clear:

- Prioritize Specialized Encoders: For high-throughput, low-latency NLU tasks like intent classification and slot filling, the optimal technical choice remains a fine-tuned encoder-only model (like BERT or RoBERTa). They offer superior performance on core NLU benchmarks compared to general LLMs, while mitigating the computational overhead of massive foundation models.

- Mandate Span-Based Evaluation: To ensure data integrity, always evaluate entity extraction using entity or span-based F1 metrics, moving away from potentially misleading token-based accuracy metrics.

- Invest in Data Curation: The heavy lifting of universal language representations is already done during pre-training. Strategic resources should be shifted toward the curation of high-quality, task-relevant fine-tuning data and meticulously optimizing fine-tuning hyperparameters (learning rate, batch size, etc.) to adapt the model perfectly to your domain.

- Leverage Ecosystem Tools: Use established open-source frameworks like the Hugging Face Transformer Framework (which centralizes model definitions, offers over 1 million checkpoints, and includes the

Pipelineclass for streamlined inference) and spaCy (crucial for high-speed, production-grade deployment of essential NLU components like NER).

Building a world-class Natural Language Understanding system today isn’t about inventing a new model from scratch; it’s about expertly leveraging the power of contextual models like BERT through precise fine-tuning and strategic architectural choices. It’s like being handed a master jeweler’s toolkit—the foundational materials are perfect; your job is to make the final, perfect cut.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the core difference between Static and Contextual Embeddings?

Static embeddings (like Word2Vec and GloVe) map a word to a single, fixed vector regardless of context, making them poor at handling polysemy (multiple meanings for one word). Contextual embeddings (like BERT) generate a unique, dynamic vector for a word based on the entire sentence it appears in, allowing the model to accurately capture the word’s meaning based on its surroundings.

How does BERT use the special $\langle\mathrm{cls}\rangle$ token in fine-tuning?

The $\langle\mathrm{cls}\rangle$ (classification) token is prepended to the input sequence. For sequence-level tasks (like intent recognition or sentiment analysis), the final hidden state representation of this specific token is considered to encode the information of the entire input text. This single vector is then fed into a classification head (extra fully connected layers) to produce the output label.

What are the main limitations of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) in sequence modeling?

The main limitation is the vanishing gradient problem. During training, especially with long sequences, the gradients used for updating model weights diminish rapidly as they propagate backward through time. This results in “short-term memory,” where the network struggles to learn long-range dependencies because the weights corresponding to tokens early in the sequence receive weak updates.

What is the “minimal architecture change” required when fine-tuning BERT?

The minimal architectural change required when adapting BERT for a downstream NLU task is the addition of extra fully connected layers (sometimes called a classification head). During supervised learning, the parameters of these new layers are learned from scratch, while all the parameters in the large, pretrained BERT model are simultaneously fine-tuned to the specific task.

Why are few-shot Retrieval-Based Frameworks useful for NLU?

Retrieval-based frameworks are useful for few-shot learning (adapting to new domains with minimal training examples) because they avoid the instability of retraining a massive model on scarce data. They work by matching token spans in the input query to the most similar labeled examples in an external index. This approach minimizes retraining, provides intrinsic interpretability (the retrieved example serves as an explanation), and is robust against overfitting.